Statistics Transnational Adoptions to Sweden

Statistics Transnational Adoptions To Sweden 1969-2022

This data is sourced from the official website of The Family Law and Parental Support Authority (Myndigheten för Familjerätt och föräldraskapsstöd, MfoF) 2025-03-03. This data include all people born outside the Nordic countries who have been sent to Sweden for adoption. This data should cover most transnational adoptions to Sweden, including adoptions facilitated by adoption agencies as well as adoptions processed privately.

You can see separate data for transnational adoptions facilitated by Sweden’s largest adoptions agency Adoptionscentrum here.

Total Adoptions Per Year

This chart visualizes the number of international adoptions to Sweden per year from 1969 to 2022. The data highlights key trends in adoption over time:

- Peak Years (Late 1970s – 1980s): The highest number of international adoptions occurred between the late 1970s and mid-1980s, with yearly totals exceeding 1,600–1,800 adoptions.

- Lower plataue duing 1990s to mid 2000s: From the early 1990s onward, adoption numbers decreased and plateaued on a lower level compared to the peak years of the 1970s and 1980s. This shift is likely due to changes in international adoption policies, increased regulations, and efforts to prioritize domestic adoptions in sending countries.

- Significant Drop After 2010: A steep decline is visible from 2010 onwards, with adoptions falling to a fraction of previous levels.

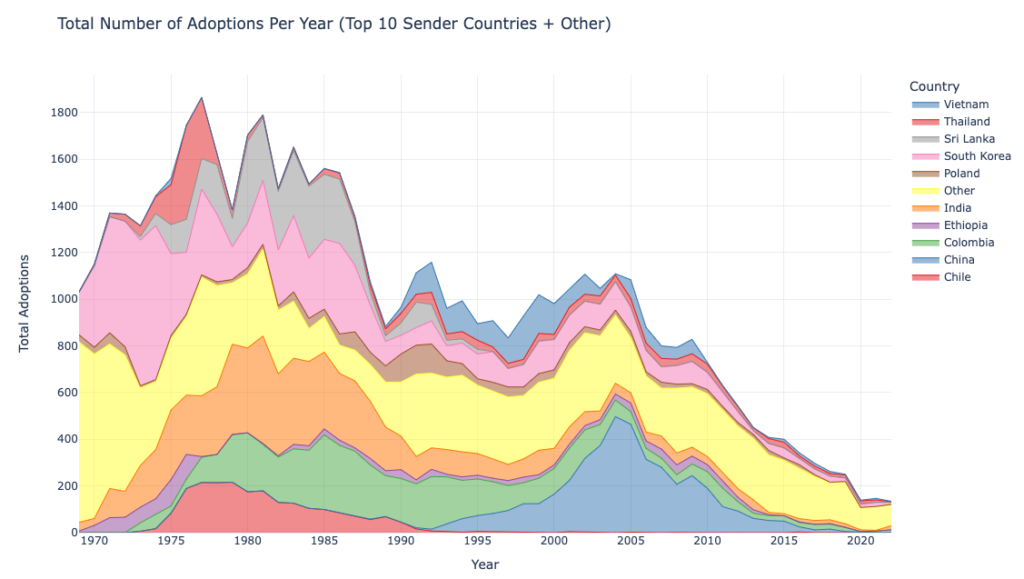

Total Adoptions by Country Per Year

This stacked area chart illustrates the number of international adoptions to Sweden per year, broken down by the top 10 sending countries. You can click on the country names in the legend (right side) to show or hide specific countries, allowing you to explore trends for individual countries.

- South Korea, Colombia, and India were dominant sender countries, particularly during the 1970s and 1980s.

- China’s international adoption peak occurred in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

- A sharp decline is seen after 2010, mirroring the global reduction in intercountry adoptions due to increased regulation, ethical concerns, and prioritization of domestic adoption in sending countries.

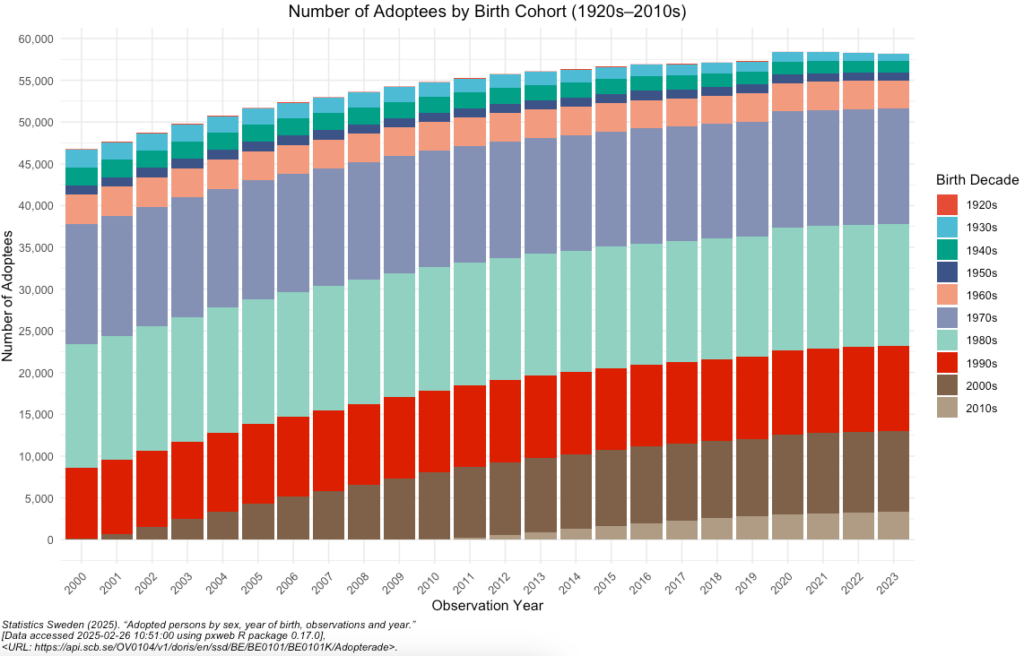

Cumulative Adoptions Over Time

This chart shows the total number of international adoptions to Sweden over time, displaying a steady increase in the number of adoptees. This chart highlights the long-term impact of international adoption policies and the shift in global adoption practices over time.

- Rapid Growth (1970s–1980s): The cumulative number of adoptions grew quickly during the 1970s and 1980s, reflecting Sweden’s high adoption rates during this period. This was when large numbers of children from countries like South Korea, Vietnam, and Colombia were adopted.

- Slower Growth (1990s–2000s): The rate of increase slowed down after the 2000s, indicating a decline in new international adoptions.

- Increasingly Slower Growth After 2010: The curve flattens in the 2010s, showing that very few new international adoptions have been recorded in recent years. This aligns with the tightening of international adoption regulations and shifting policies prioritizing domestic solutions for children.

Cumulative Adoptions by Country

This chart illustrates the cumulative number of international adoptions to Sweden over time, broken down by country. Each layer represents adoptees from a specific country, showing their contribution to Sweden’s adoption history. Click on country names in the legend to explore individual adoption trends and see how different countries contributed to Sweden’s adoption history.

Top 20 Sending Countries

This bar chart presents the 20 most common sending countries for international adoptions to Sweden between 1969 and 2022.

- South Korea is the largest source country, accounting for 20.1% of all recorded adoptions. This reflects the country’s long history of transnational adoption industry.

- India, Colombia, and China follow as major sending countries, each representing a significant share of total adoptions.

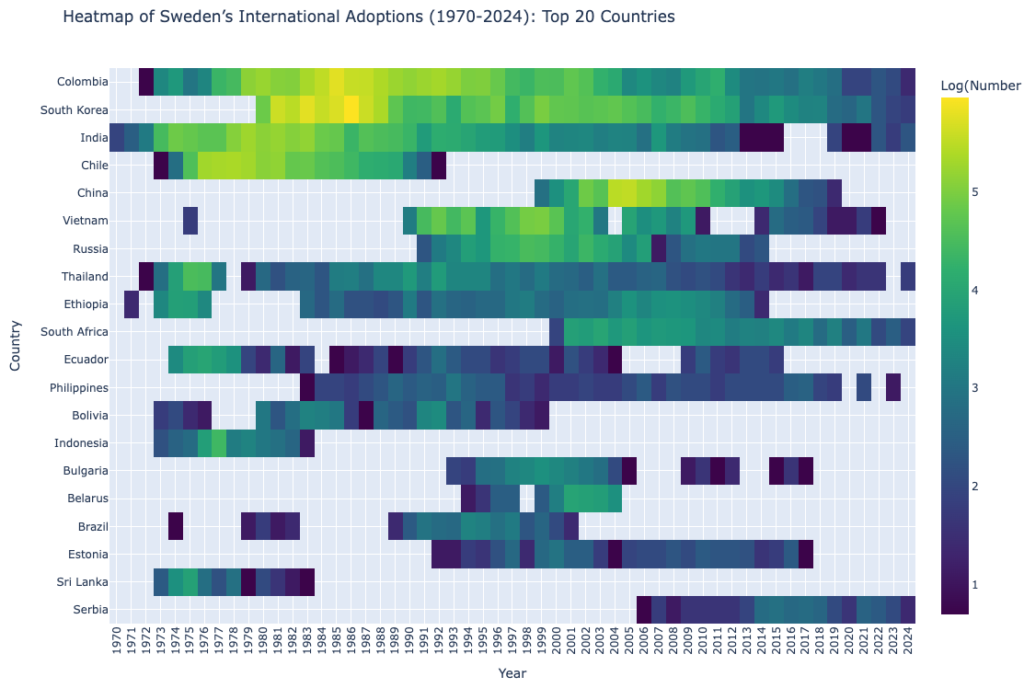

Adoption Heatmap

This heatmap provides a historical overview of international adoptions to Sweden from the top 20 sending countries over the period 1969–2022. It allows us to see when different countries were major sources of adoptees and how adoption patterns shifted over time. Hover over a tile to see the number of adoptions from a specific country a specific year.

How to Read the Heatmap

- Each row represents a country, while the columns represent years from 1969 to 2022.

- The color intensity represents the number of adoptions, with darker shades indicating fewer adoptions and brighter shades (yellow/green) indicating more adoptions.

- White gaps indicate years where no recorded adoptions occurred from a specific country.

Why Log Scale?

- The color scale uses a logarithmic scale, meaning that differences are more pronounced for smaller values while still capturing trends for countries with high adoption numbers.

- This makes it easier to compare countries that had both low and high adoption rates over time.

Statistics Transnational Adoptions to Sweden Read More »